India’s Nuclear Sector: Opening Gates to Global Partnerships?

India’s quest for energy independence is taking a pivotal turn, with legislative efforts underway to revamp two foundational laws governing its atomic energy sector. These proposed amendments aim to iron out long-standing investor anxieties and finally unlock India’s civil nuclear potential on the global stage.

At the heart of the debate lies the **Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act, 2010 (CLNDA)**. Enacted to provide a compensation mechanism for nuclear accident victims, the CLNDA inadvertently became a formidable barrier. Foreign giants like US-based **Westinghouse Electric** and French nuclear firm **Framatome**, alongside domestic players such as **L&T** and **Walchandnagar Industries**, have consistently cited a crucial provision – the “right of recourse” of the operator – as a major disincentive. This clause, specifically Section 17(b) of the CLNDA, allows an operator (typically state-owned **Nuclear Power Corporation of India Ltd (NPCIL)**) to transfer liability to suppliers in the event of a nuclear incident caused by defective equipment or sub-standard services. The fear of open-ended financial exposure has kept international capital and cutting-edge technology at bay.

The proposed legislative adjustments are set to dilute Section 17(b), aligning India’s framework more closely with international norms, particularly the **1997 Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage (CSC)**, which India ratified in 2016. Furthermore, significant changes to the **Atomic Energy Act, 1962**, currently restrict nuclear power plant operations to state-owned entities like **NPCIL** and **NTPC Ltd**. The amendments seek to open doors for private companies, and potentially even foreign players, to participate as operators, possibly even taking minority equity stakes.

This bold reform push isn’t just about energy; it’s a strategic move. It could breathe new life into the long-stalled **Indo-U.S. civil nuclear dialogue**, nearly two decades after its initial promise. Beyond that, New Delhi envisions this as a key component of a broader trade and investment outreach with **Washington D.C.**, potentially culminating in a much-anticipated trade pact. Recent approvals, such as the US Department of Energy’s authorization for **Holtec International** to transfer Small Modular Reactor (SMR) technology to its Indian subsidiary **Holtec Asia**, and partners like **Tata Consulting Engineers Ltd** and **Larsen & Toubro Ltd**, signal a thawing of previous rigidities, hinting at a more collaborative future for India’s nuclear aspirations.

Western Ghats: Reclaiming Green with Community Power

The verdant expanse of the **Western Ghats**, a global biodiversity hotspot, faces an ongoing struggle for preservation. Environmentalist **Madhav Gadgil** has been a vocal critic, contending that official data from the **Forest Survey of India (FSI)** is not only outdated and aggregated but also “deliberately distorted.” He argues that the traditional **Forest Department (FD)**, which he controversially labels as “anti-science, anti-nature, anti-people,” is fundamentally ill-equipped to safeguard and re-green this critical ecological region.

Gadgil’s critique gains historical context from the early days of satellite imagery. Back in 1972, soon after **Satish Dhawan** took the helm of the **Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO)** and the **Landsat programme** offered its first Earth images, the **National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC)** in **Hyderabad** revealed stark discrepancies between actual forest cover and official FD records. Today, with the advent of accessible, real-time satellite data like **Google Earth**, the delay and aggregation in FSI data seem inexcusable.

The answer, according to Gadgil and a growing chorus of advocates, lies in a paradigm shift: a science-based, nature-centric, and, crucially, people-oriented approach. A shining example of this is the “Pachgaon way.” This village, leveraging its **Community Forest Rights (CFR)** under the **Forest Rights Act of 2006** over 1,000 hectares, has demonstrably transformed its local environment and economy. Through sustainable bamboo sales, the people of **Pachgaon** have secured livelihoods, even abandoning the traditional practice of burning **tendu leaves** for income, despite its previous profitability. They have also voluntarily designated 30 hectares as a sacred grove, fostering robust forest growth and significant carbon sequestration. This localized empowerment has not only rejuvenated the ecosystem but also instilled self-respect and reduced outward migration, proving that conservation thrives when communities are at its core. The debate over the **Gadgil** and **Kasturirangan Committees’** recommendations continues to underscore the need for a balanced approach that respects both ecological sensitivity and local developmental needs.

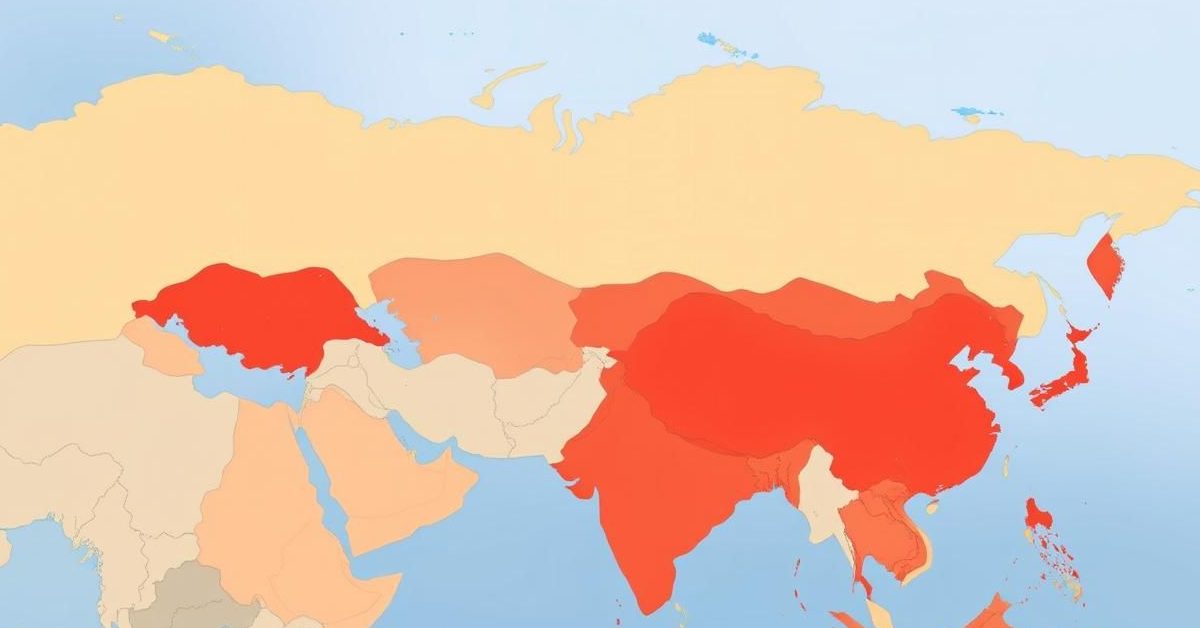

India’s Trade Balancing Act: Navigating the China Challenge

India finds itself at a delicate intersection in its trade relationship with **China**: an undeniable economic necessity grappling with escalating national security concerns. While bilateral commerce continues to flourish, hitting an approximate **US$127.7 billion in FY2024–25**, making China India’s second-largest trading partner, this volume comes at a significant cost. India’s trade deficit with China reached a record high of **US$99.2 billion**, revealing deep structural dependencies, particularly in critical sectors like technology and pharmaceuticals.

This imbalance is further complicated by Beijing’s overt support for **Pakistan**, a nation India views as a direct security threat. In response, New Delhi has meticulously crafted a “China-plus-one” playbook. This multi-pronged strategy is anchored in diversification, robust industrial policy, and regional recalibration.

The United States has emerged as India’s largest goods-trade partner for the fourth consecutive year, with bilateral commerce reaching **US$131.8 billion in FY 2024-25**. This burgeoning partnership is underpinned by initiatives like the **Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technologies (iCET)**, fostering joint projects in semiconductors, AI, and space. Similarly, **Japan** plays a pivotal role, underwriting supply-chain security and industrial upgrading through collaborations like the **Supply-Chain Resilience Initiative (SCRI)** with Australia, targeting crucial sectors like electronics and batteries. Over four-fifths of Japanese firms in India, according to **JETRO**, plan to expand, reflecting deep confidence. Southeast Asia forms the third pillar, with India actively reviewing the **ASEAN-India Trade in Goods Agreement** and pursuing niche collaborations, such as semiconductor talks with **Singapore** and defense manufacturing ties with **Indonesia**.

Domestically, the “Make in India” initiative and **Production-Linked Incentive (PLI)** schemes, spanning 14 sectors with approved investments of around **US$18.7 billion**, are turbocharging local manufacturing. India has become the world’s second-largest mobile phone producer, with smartphone exports surging to **US$24.1 billion** in FY 2024-25, leap-frogging traditional exports. This dual strategy aims not just at import substitution but at positioning India as a competitive player in high-value, sunrise industries.

The Jute Paradox: Strained Ties and Trade Curbs with Bangladesh

Recent decisions by New Delhi to restrict imports of certain jute products and woven fabrics from **Bangladesh** via land routes signal deepening strains in bilateral relations. While official reasons include common malpractices by Bangladeshi exporters and the influx of cheap, subsidized imports harming Indian farmers, an underlying geopolitical concern is **Dhaka’s** growing proximity to **Beijing**.

The **Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT)**’s notification permits entry only through the **Nhava Sheva seaport** in Maharashtra, though it exempts Bangladeshi goods transiting through India to **Nepal** and **Bhutan**. The restricted items include a range of jute products, flax, and woven fabrics.

Despite **SAFTA** provisions granting duty-free access, the Indian jute industry, primarily located in states like **West Bengal, Bihar, Assam, and Odisha**, has long suffered from what it describes as “dumped and subsidized imports.” India had previously imposed anti-dumping duties (ADD) on Bangladeshi jute, but officials report that large exporters frequently circumvented these measures through technical exemptions, mis-declarations, and exporting beyond their production capacity.

The consequences for Indian farmers and the domestic jute industry are severe. Imports, which saw only a marginal decline post-ADD, have since risen, leading to jute prices falling below the **Minimum Support Price (MSP)** of **Rs 5,335 per quintal** for FY 2024-25. This has triggered a “vicious payment/liquidity cycle,” forcing six mills to close with substantial dues. The Indian government asserts that Bangladesh continues to incentivize exports, particularly of value-added jute products, exacerbating the problem and threatening the long-term viability of Indian mills, which collectively provide direct employment to over 4 lakh workers.

Global Food Security: China’s Fertilizer Grip and India’s Vulnerability

China’s influence on global supply chains extends beyond rare earth elements and critical minerals; it now significantly impacts agricultural essentials, specifically **Di-ammonium Phosphate (DAP)**, a crucial fertilizer for crop development. India, heavily reliant on imported DAP for its agricultural backbone, is feeling the squeeze.

Opening stocks of DAP in India for the current **kharif (monsoon) planting season** on June 1 stood at a concerning 12.4 lakh tonnes (lt), significantly lower than the 21.6 lt just a year prior. This stark deficit is largely attributed to China’s drastic reduction in DAP exports, which were once a primary source for India. Imports from China plummeted from 22.9 lt in 2023-24 to a mere 8.4 lt in 2024-25, with no shipments recorded since the beginning of this calendar year.

Beijing’s export curbs stem from a dual objective: ensuring domestic supply for its own farmers and meeting the burgeoning demand for phosphates in the production of **Electric Vehicle (EV) batteries**. This strategic shift has forced Indian importers to scramble for alternative sources from countries like **Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Russia**, and **Jordan**. However, none of these nations have been able to fully compensate for the massive void left by China, posing a serious challenge to India’s food security and agricultural planning.

The situation also reignites debates within India about the judicious use of fertilizers. While DAP (18% nitrogen, 46% phosphorous) and urea (46% nitrogen) are widely used, many agronomists advocate for “balanced fertilization” – using complex fertilizers with nutrients in optimal proportions for plant absorption. Capping or reducing DAP consumption could lead to more efficient resource utilization and a reduction in India’s reliance on expensive, imported agricultural inputs, highlighting a path toward greater self-reliance in a volatile global market.

Invisible Threats: The Growing Peril of GPS Interference

Recent alarming incidents, from a **Delhi-Jammu Air India Express flight** forced to turn back due to navigation issues to a collision in the **Strait of Hormuz** and a container ship running aground near **Jeddah**, share a common, insidious thread: **GPS interference**. This invisible threat poses a significant risk to global transportation, both in the air and at sea.

GPS interference manifests primarily in two forms: **jamming** and **spoofing**. **GPS jamming** involves a device emitting powerful radio signals on GPS frequencies, effectively overpowering and disrupting the weaker satellite signals. This renders GPS receivers unable to pinpoint their location or time. In contrast, **GPS spoofing** is more deceptive. It involves transmitting false GPS signals that trick a receiver into believing it is in a different location or time than it actually is, overriding or blocking genuine satellite data. While often used interchangeably, jamming causes a loss of signal, whereas spoofing provides convincing, yet erroneous, data.

The consequences of such interference are dire. As **Air Marshal Bhushan Gokhale (retd)**, former vice-chief of Air Staff, highlighted, “Spoofing can cause a pilot to misjudge the aircraft’s position, increasing the chance of collisions with terrain or other aircraft.” For maritime vessels, the loss of situational awareness can lead to groundings or collisions, throwing entire maritime operations into disarray. Beyond individual incidents, GPS interference can cascade into broader systemic failures in critical infrastructure, including air traffic control and port operations.

While malicious attacks from state actors in conflict zones, such as the ongoing **Russia-Ukraine war** or tensions in the **Red Sea**, are a major concern, interference can also stem from less sinister causes, including electromagnetic radiation from nearby devices, adverse atmospheric conditions, or solar flares. To counter these threats, pilots and mariners rely on backup systems. **Inertial Navigation Systems (INS)** use gyroscopes and accelerometers to track position from the last known location. Ground-based radio navigation systems like **VHF Omnidirectional Range (VOR)** and **Distance Measuring Equipment (DME)** provide additional cross-checks. Significantly, India has deployed its indigenous **Navigation with Indian Constellation (NavIC)**, developed by the **Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO)**, designed to offer precise positioning and timing services across India and extending 1,500 km beyond its borders, offering a vital layer of redundancy against global GPS vulnerabilities.