The Invisible Invaders: How Microplastics Are Silently Threatening Your Heart Health

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain a grim global reality, claiming millions of lives each year. While genetics and lifestyle factors are well-known contributors, a more insidious threat is emerging from our environment: microplastics. These minuscule plastic fragments, now ubiquitous in our world, are increasingly linked by scientific research to a worsening of heart health and a host of other critical medical conditions.

Imagine tiny, unseen particles infiltrating your body with every breath you take, every sip of water, every meal. This isn’t science fiction; it’s the daily reality of microplastic exposure. From the fish we consume to the air circulating in our homes, these persistent pollutants are finding their way into our most vital organs, including the very core of our circulatory system.

Understanding the Unseen Enemy: What Are Microplastics?

Microplastics are defined as plastic particles less than five millimeters in size – smaller than a sesame seed. Their pervasive presence has become one of the most pressing environmental concerns of our time, contaminating everything from the deepest oceans to the highest mountain peaks.

These tiny invaders aren’t all created equal. They fall into two main categories: “primary microplastics,” which are intentionally manufactured to be small, like those once found in certain cosmetic exfoliants, and “secondary microplastics,” which arise from the breakdown of larger plastic items over time. Think of a discarded plastic bottle slowly degrading under the sun and waves, shedding countless microscopic fragments.

Common types of plastic that degrade into these harmful particles include Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET), often used in beverage bottles; Polystyrene (PS), found in disposable cutlery; Polypropylene (PP), prevalent in food containers; Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC), used in pipes; and Polyethylene (PE), common in plastic bags. These materials are famously non-biodegradable, meaning they persist in our environment for centuries, slowly breaking down into smaller and smaller, yet still environmentally persistent, pieces.

The scale of the problem is staggering. Global plastic production has surged past 400 million tons annually, with projections suggesting it could exceed a billion tons by 2060. This relentless output guarantees an ever-increasing deluge of microplastics into our ecosystems and, inevitably, into our bodies.

Ubiquitous Invaders: How Microplastics Permeate Our Systems

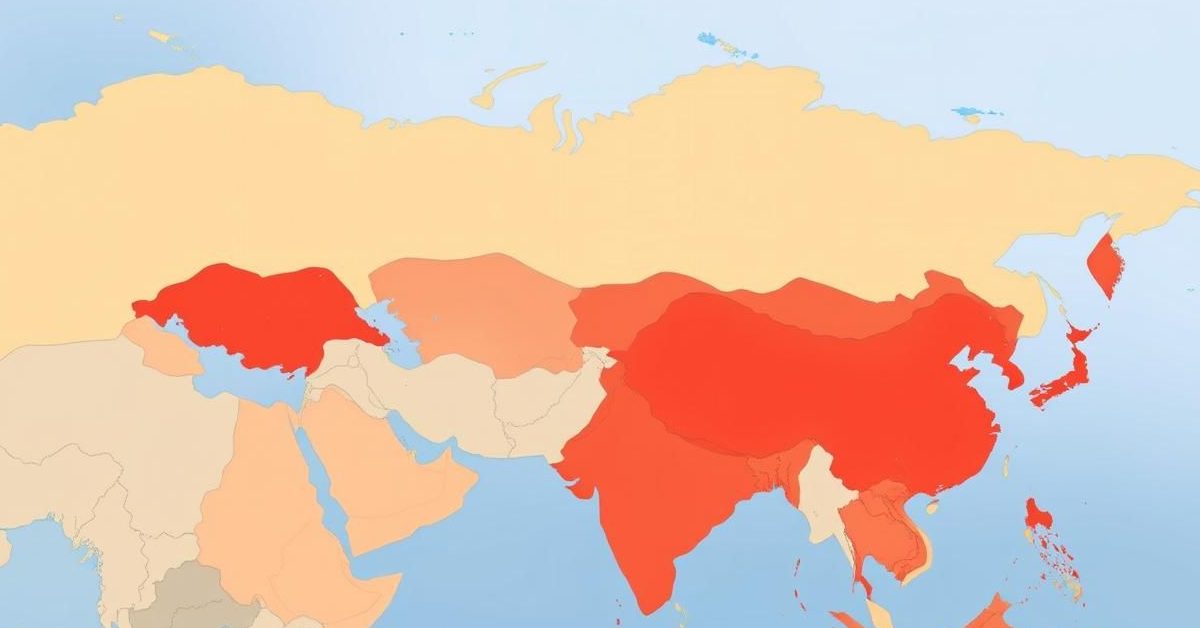

Microplastics are now truly everywhere, reaching even the most remote, uninhabited corners of the planet. This widespread contamination impacts all ecosystems – terrestrial, aquatic, and atmospheric – posing a significant threat to plants, animals, and, critically, humans.

Beyond their inherent toxicity, microplastics act as carriers, attracting and transporting other environmental pollutants. Heavy metals, persistent organic pollutants (POPs), and various toxic additives like plasticizers and stabilizers used during their manufacturing processes hitch a ride on these tiny particles, amplifying their potential harm once inside a living organism.

For humans, exposure pathways are numerous and unavoidable. We inhale them from the air, ingest them through contaminated drinking water, sea salt, crop plants, and fishery products. Once inside, these microscopic particles don’t just pass through; they can accumulate in various organs and, alarmingly, enter the bloodstream, circulating throughout the body.

The evidence of their infiltration is growing. Microplastics have been detected in a startling array of human biological fluids and organs, including semen, breast milk, urine, arteries, the brain, liver, lungs, heart, and even the placenta. This widespread presence underscores their potential for systemic damage.

A Silent Scourge: Widespread Health Impacts Beyond the Heart

Laboratory studies, both in vitro (on cell lines) and in vivo (on animals like rats, mice, and zebrafish), along with emerging human studies, have illuminated the toxic effects of microplastics. The list of potential health repercussions is extensive and concerning.

Beyond cardiovascular concerns, microplastics have been linked to gut dysfunction, respiratory issues, kidney and liver damage, reproductive and developmental problems, and even neurological disorders. This broad spectrum of potential harm highlights microplastics not just as a specific organ threat but as a systemic challenge to human health.

The Heart of the Matter: Microplastics and Cardiovascular Disease

The World Health Organization (WHO) consistently identifies cardiovascular diseases as a leading cause of non-communicable disease mortality. In India, for instance, CVDs accounted for approximately 27% of all deaths in 2016. This category encompasses a range of disorders, from hypertension and stroke to myocardial infarction (heart attack) and congenital heart defects.

A heart attack, caused by an interruption of blood flow to the heart muscle, remains one of the deadliest conditions globally. The societal burden of CVDs extends far beyond mortality and morbidity; they impose immense out-of-pocket medical expenses, lead to job loss, contribute to mental health issues, and cause significant financial distress for families.

Given this immense burden, understanding how emerging environmental factors like microplastics influence cardiovascular health is paramount. Detecting microplastics within the human body offers a crucial opportunity to identify vulnerable patients and potentially mitigate risks, thereby reducing mortality and alleviating healthcare costs for both individuals and national health systems.

While extensive human studies specifically on cardiotoxicity in India are yet to be conducted, global research paints a concerning picture. Recent international studies suggest a potential link between microplastic exposure and the severity of CVDs. These studies indicate that microplastics can cause “cardiotoxicity”—direct damage to the heart muscle or its function. This damage can manifest as abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmias), heart failure, and structural impairments to heart tissue.

Remarkably, microplastics of varying shapes, sizes, and quantities have been found directly within a range of cardiac tissues, including the pericardium (the sac surrounding the heart), epicardial and pericardial adipose tissue (fatty tissues around the heart), the myocardium (heart muscle), and the left atrial appendage. They have also been identified in critical arteries such as the coronary arteries (supplying the heart), cerebral arteries (supplying the brain), carotid arteries (supplying the head and neck), and the aorta (the body’s main artery). The types of plastics detected frequently include PVC, PET, PE, and PP—the same common plastics that make up so much of our daily lives.

The Atherosclerosis Connection: Choking Our Arteries

The insidious impact of microplastics extends to their association with adverse biological effects, notably oxidative stress and inflammation. These cellular responses are crucial drivers in the development and progression of atherosclerosis, a dangerous condition where plaque accumulates within the arteries.

This plaque, a sticky concoction of cholesterol, fatty substances, and calcium, gradually narrows the arterial lumen, impeding the vital flow of blood to the heart muscle. Should this plaque rupture, it can trigger the formation of a thrombus, or blood clot, which can completely block the artery. This blockage, starving the heart muscle of oxygen and nutrients, leads to cardiac cell injury and death—the devastating event known as a myocardial infarction, or heart attack.

Disturbing research indicates higher concentrations of microplastics in cardiac patients compared to healthy control groups. Furthermore, the presence of microplastics in arteries has been directly linked to an increased risk of major adverse clinical outcomes during follow-up periods. These outcomes include death, recurrent heart attacks, heart failure, reduced cardiac function, and stroke. Alarmingly, the severity of ischemic stroke has also been found to correlate with the concentration of microplastics in affected individuals.

The Indian Context: Addressing Research Gaps and Future Hopes

Despite the growing body of global evidence, a significant limitation remains: the generalizability of these findings to the diverse Indian population. Most existing studies have used relatively small sample sizes and may not adequately represent the unique environmental exposures and health profiles prevalent in India. Crucially, a definitive cause-and-effect (causal) relationship between microplastics and cardiovascular diseases has yet to be unequivocally established.

It’s important to acknowledge that microplastics could potentially be “bystanders,” with confounding variables—such as exposure to other environmental pollutants or co-existing health conditions like diabetes—also contributing to the severity of CVDs. Therefore, future research must prioritize comprehensive cohort studies across various Indian populations, accounting for differing levels of microplastic exposure. Such studies are vital for solidifying a causal link within the Indian context.

Global Action and Local Efforts: Turning the Tide on Plastic Pollution

Recognizing the global scale of the plastic pollution crisis, the United Nations Environment Assembly passed a landmark resolution in 2022. This led to the formation of an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC), tasked with developing a legally binding international treaty to address plastic pollution comprehensively. While a consensus is still being sought, the upcoming INC-5.2 meeting in August 2025 offers renewed hope for the agreement on a Global Plastic Treaty, one that considers the concerns of all stakeholders and accelerates worldwide efforts to curb this menace.

In India, proactive steps have already been taken to mitigate plastic misuse. A nationwide ban on single-use plastics came into effect on July 1, 2022, demonstrating a commitment to reducing plastic waste at its source. Further progress can be made by rigorously implementing the “3 Rs” of waste management: Reduce, Reuse, Recycle. This foundational principle can significantly diminish plastic pollution.

Beyond traditional methods, encouraging the adoption of environment-friendly biodegradable bioplastics, such as polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), offers a promising alternative. Crucially, increasing public awareness about the toxic effects of plastics and microplastics is paramount. An informed populace is more likely to reduce their plastic consumption and advocate for policies that protect both human health and the planet from these pervasive, invisible threats.